Bit Hacks

1. Preliminary

Bit manipulation is common in C / C++. Sometimes it helps speed up our program and save memory usage. This post summarized some interesting tricks about bit manipulation. Before learning them, the basic concept of binary representation is acquired. I wrote a post related to the two’s complement representation which is worth reading.

2. Hacks

2.1 Toggle the k-th bit

y = x ^ (1 << k);

2.2 Extract or set a bit field

Extract a bit field from a word x

y = (x & mask) >> shift

Set a bit field in a word x to value y

x = (x & ~mask) | (y << shift)

2.3 No-temp swap

Swap x and y without using a temporary

x = x ^ y;

y = x ^ y;

x = x ^ y;

Why it works?

(x ^ y) ^ y => x

2.4 No-branch minimum of two integers

Find the minimum r of two integers x and y

r = y ^ ((x ^ y) & -(x < y));

Why it works?

-1 is represented in all 1’s in two’s complement representation.

if (x < y) is true, the value in the parentheses should be (x ^ y) & (-1), that is (x ^ y). And y ^ (x ^ y) is x.

if (x < y) is false, the value in the parentheses should be (x ^ y) & (0), that is 0. And y ^ 0 is y.

2.5 Merging two sorted arrays

void merge(int* A, int* B, int* C, int na, int nb){

while(na > 0 && nb > 0){ // branch 1

if(*A <= *B){ // branch 2

*C++ = *A++; na--;

}else{

*C++ = *B++; nb--;

}

}//while

while(na > 0){ //branch 3

*C++ = *A++; na--;

}

while(nb > 0){ //branch 4

*C++ = *B++; nb--;

}

}

The above C++ code is the common implementation of merging two sorted arrays. There are 4 branches totally (annotated in comments). Obviously, branch 1, branch 3, and branch 4 are predictable while branch 2 is not. An optimized version of the code is shown below.

void merge_opt(int* A, int* B, int* C, int na, int nb){

while(na > 0 && nb > 0){ //branch 1

int cmp = (*A <= *B);

int min = *B ^ ((*A ^ *B) & (-cmp));

*C++ = min;

A += cmp; na -= cmp;

B += !cmp; nb -= !cmp;

}

while(na > 0){ //branch 3

*C++ = *A++; na--;

}

while(nb > 0){ //branch 4

*C++ = *B++; nb--;

}

}

The branch 2 is optimized with bit hacks and no branching in the first while loop anymore. However, I used two arrays of size 10e7 to test the two functions, and the running times are as follows.

Branching : 0.045227s

Branchless : 0.087169s

Even though the unpredictable branch was removed, the running time of the optimized version is slower than the branching version. Why? The reason is that modern compilers can perform the optimization better than we can!!

So, why should we learn bit hacks if they don’t even work?

- Because the compiler does the optimization works and learning bit hacks can help us understanding what the compiler is doing when we read the assembly code.

- Sometimes the compiler doesn’t optimize for us and we have to do it by hand.

- Because they’re fun!!

2.6 Round up to the power of 2

Compute \(2^{\lceil \lg n \rceil}\)

uint64_t n;

--n;

n |= n >> 1;

n |= n >> 2;

n |= n >> 4;

n |= n >> 8;

n |= n >> 16;

n |= n >> 32;

++n;

why it works?

Assume the position of the 1 in the answer is \(i\). The above code set all the positions of the right side of \(i\) to 1 and increment.

Why decrement?

The \(n\) may be the power of 2.

2.7 Least-significant 1

Compute the mask of the least-significant 1 in word x

r = x & (-x)

Why it works?

\[x + (\sim x) = -1\] \[-x = (\sim x) + 1\]2.8 Bit vector representation

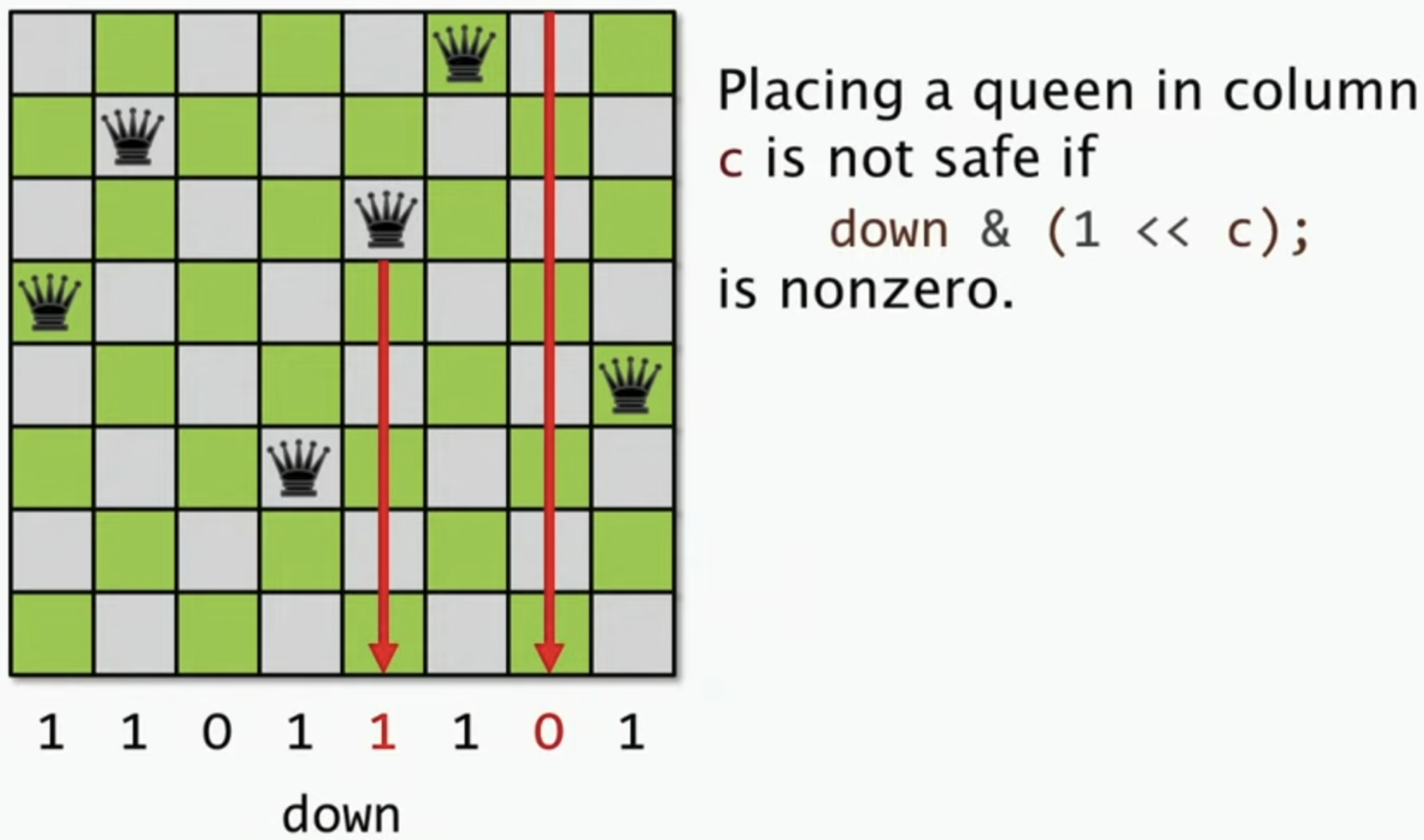

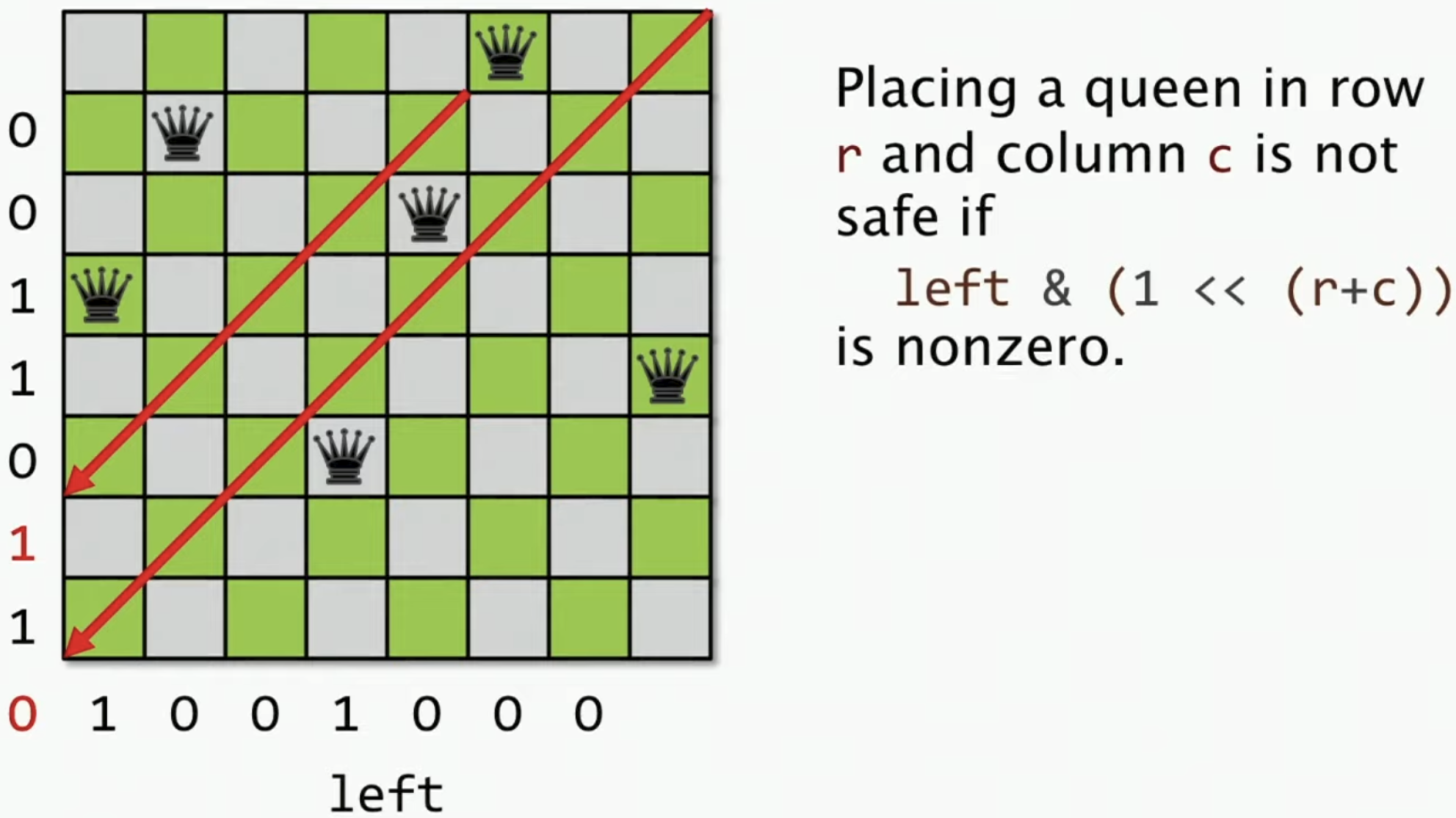

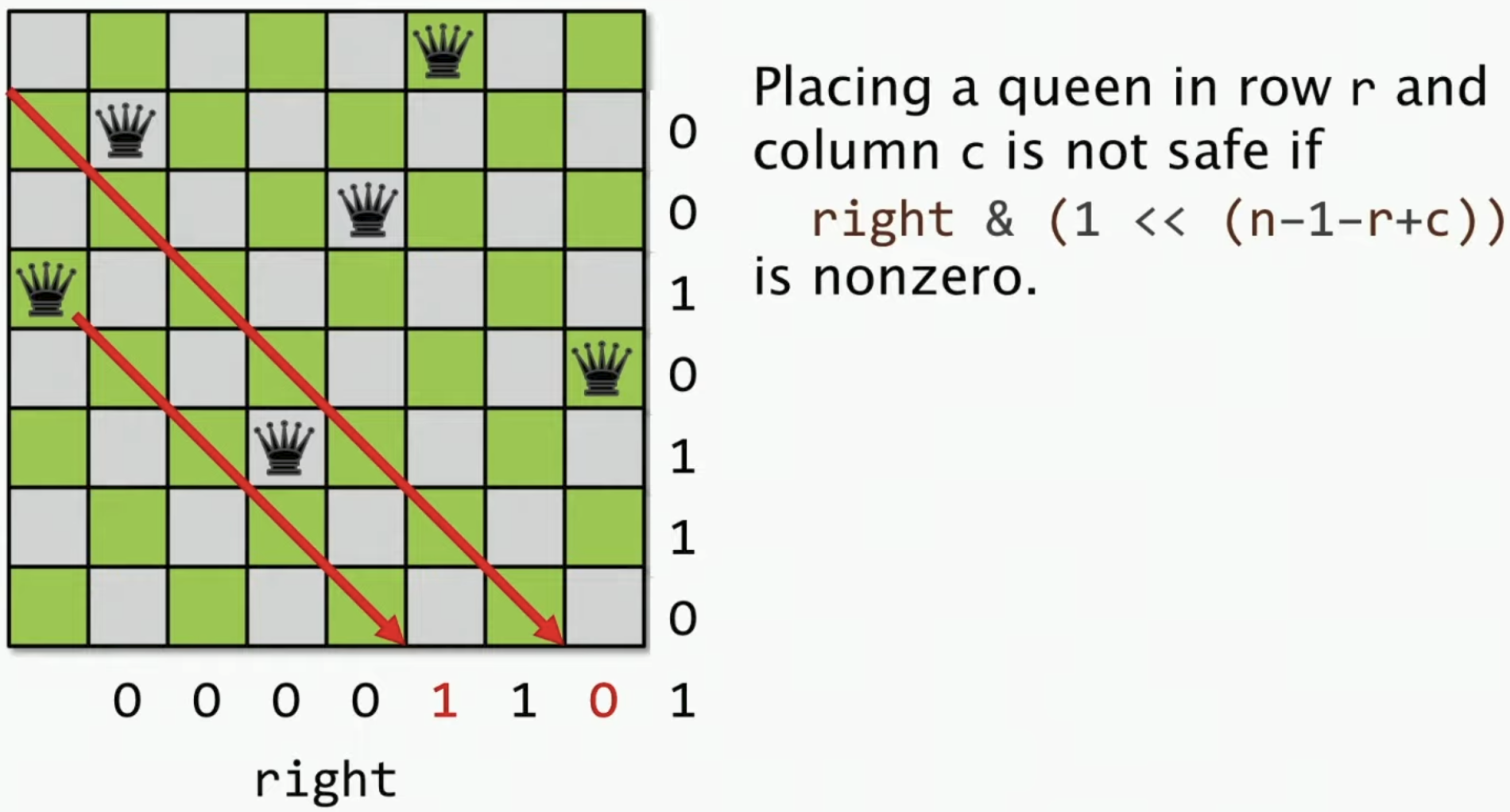

Solving N queens problem with 3 bit vectors of size n, 2n-1, 2n-1

Originally, \(n^2\) of bytes are needed to represent the board. And now 3 bit vectors are enough.

Apply this tricks to solve Leetcode 52. N-Queens II.

class Solution {

public:

int totalNQueens(int n) {

int down = 0, left = 0, right = 0;

return bitHacksDfs(down, left, right, 0, n);

}

int bitHacksDfs(int down, int left, int right, int row, int n){

int ret = 0;

if(row == n)

return 1;

for(int col=0; col<n; ++col){

bool downCheck = (1 << col) & down;

bool leftCheck = (1 << (row+col)) & left;

bool rightCheck = (1 << (n-1-row+col)) & right;

if(!downCheck && !leftCheck && !rightCheck){

down = down | (1 << col);

left = left | (1 << (row+col));

right = right | (1 << (n-1-row+col));

ret += bitHacksDfs(down, left, right, row+1, n);

down = down ^ (1 << col);

left = left ^ (1 << (row+col));

right = right ^ (1 << (n-1-row+col));

}

}

return ret;

}

};

Runtime: 0 ms, faster than 100.00% of C++ online submissions for N-Queens II.

Memory Usage: 5.8 MB, less than 95.74% of C++ online submissions for N-Queens II.

2.9 Log base 2 of a power of 2

Compute \(\lg x\) where \(x\) is the power of 2

#include<stdlib.h>

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdint.h>

int lgx(int x){

const uint64_t deBruijn = 0x022fdd63cc95386d;

const int convert[64] = {

0, 1, 2, 53, 3, 7, 54, 27,

4, 38, 41, 8, 34, 55, 48, 28,

62, 5, 39, 46, 44, 42, 22, 9,

24, 35, 59, 56, 49, 18, 29, 11,

63, 52, 6, 26, 37, 40, 33, 47,

61, 45, 43, 21, 23, 58, 17, 10,

51, 25, 36, 32, 60, 20, 57, 16,

50, 31, 19, 15, 30, 14, 13, 12

};

return convert[(x * deBruijn) >> 58];

}

int main(){

int test_cases[14] = {1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048, 4096, 8192};

for(int i=0; i<14; ++i){

printf("%4d is 2^%d\n", test_cases[i], lgx(test_cases[i]));

}

return 0;

}

The output:

1 is 2^0

2 is 2^1

4 is 2^2

8 is 2^3

16 is 2^4

32 is 2^5

64 is 2^6

128 is 2^7

256 is 2^8

512 is 2^9

1024 is 2^10

2048 is 2^11

4096 is 2^12

8192 is 2^13

Why it works?

That is the magic of deBruijn sequence!!

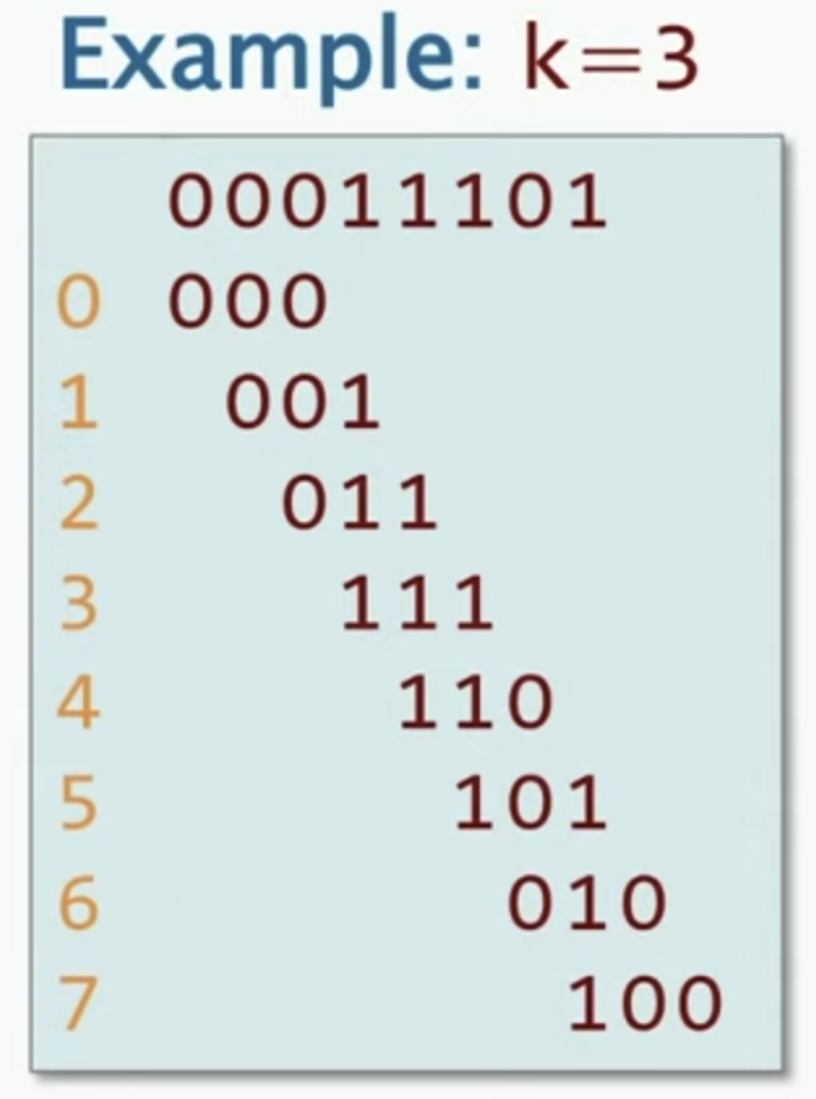

A deBruijn sequence \(s\) of length \(2^k\) is a cyclic 0-1 sequence such that each of the \(2^k\) 0-1 strings of length \(k\) occurs exactly once as a substring of \(s\).

Let see an example of deBruijn sequence with length 8 and \(k=3\).

The deBruijn sequence is \(0b00011101\).

The substrings are {000, 001, 011, 111, 110, 101, 010, 100} that is labeled with 0 to 7. Obviously, they don’t overlap and occur exactly once.

And we can build a map as below

const int convert[8] = {0, 1, 6, 2, 7, 5, 4, 3};

where the number in position \(i\) represents the label.

- And if we want to know the \(\lg x\) where \(x = 2^4\), multiply \(2^4\) by the above deBruijn sequence first.

- Then we extract the first \(k=3\) bits.

The 6 is the unique substring in our carefully selected deBruijn sequence.

- Finally, we get the answer by indexing the map.

In other words, since the \(0b00000110\) is the unique substring in the deBruijn sequence, that means we know exactly how much does it left shift to get this unique substring. The number of bits it shifts is the answer.

And if we expand the length of the deBruijn sequence to 64, the maximum input is \(2^{64}\).

3. Summary

The bit hacks help speed up the program at the cost of the code readability sometimes. But it is useful when the compiler doesn’t optimize for us. And finally, have fun!!

Reference

MIT 6.172 Lecture 3: Bit Hacks (The source of the pictures in this post)